As COP 26 approaches, the UK government (as President of the COP) and the UNFCCC are encouraging as many countries as possible, in accordance with Paragraph 36 of the Paris Agreement Decision Text, to communicate mid-century, long-term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies. These should ideally include a net-zero emissions goal for the same time period as such ambitious national contributions are required from all countries to meet the 1.5°C goal of the Paris Agreement. To date, about 30 such strategies have been posted on the UNFCCC website.

For India, a mid-century goal of net-zero emissions points to a fundamentally different development pathway to one that might have been imagined just a few years ago. While the busyness and intensity of traffic and commerce in Indian cities like Mumbai and Delhi give the impression of a country bound to fossil fuels, the reality is very different. With around 1.4 billion people in total and a large rural population engaged in agricultural activities, per capita CO2 emissions – at 1.8 tonnes per person in 2015 – are around a ninth of those in the USA and around a third of the global average of 4.8 tonnes per person.

However, overall, India is now the planet’s third-largest emitter of CO2, behind China and the USA. Some costs of the country’s dynamic growth are increasingly visible, namely major congestion in urban centres and declining air quality.

The emissions focus should be on where India might go, rather than where it has been. For example, there are about 3 billion tonnes of steel in use within the country, in buildings, cars, appliances, pipelines and industrial plants. But as India aspires to be a developed economy, that number will likely rise to around 15 billion tonnes. Every other country has built its steel infrastructure with coal as the energy source, but if India does the same that could add another 24 billion tonnes of CO2 to the atmosphere globally, based on production emissions of about 2 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of iron. A good proportion of this would come from smelters in India, many of which may not have even been built yet. This is 6% of the IPCC 1.5°C carbon budget globally and would create a significant emissions spike, even considering efficiency improvements in smelting and optimised recycling. It will also add to the local environmental stresses that people in India feel each and every day. So a different smelting pathway should be considered and that is just one aspect of India’s future national development.

Similarly, the Indian electricity sector is largely based on coal fired generation, but here there are visible signs of change as solar and wind become the preferred choices for new generation capacity. By 2020, India had all but met its Nationally Determined Contribution goal of 40% cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030 (solar, wind, nuclear, hydro, biomass). Whether its cars, trucks, housing, factories or commercial buildings, the story is largely the same; what is yet to come far exceeds what is already there.

This points to a strategic emissions focus for India that is very different to countries with substantial legacy infrastructure. Rather than needing to dislodge the status quo, India has the opportunity to embark on a different development pathway based around cleaner energy technologies and efficiency. These future choices will be important, not just at the national level when making important infrastructure decisions, but also in homes. At the household level, ownership of domestic appliances such as washing machines, refrigerators and air conditioners is relatively low, varying between 15% and 30%, depending on the appliance. As the country develops over the coming 30 years, appliance ownership may well head towards the 90% level seen in much of the world. Once in use these appliances will consume energy, so the choice of model and efficiency rating will be important. These appliances could add 300-500 terrawatt-hours a year to electricity demand, nearly a third of that generated in 2019, but lower efficiency choices might double this amount.

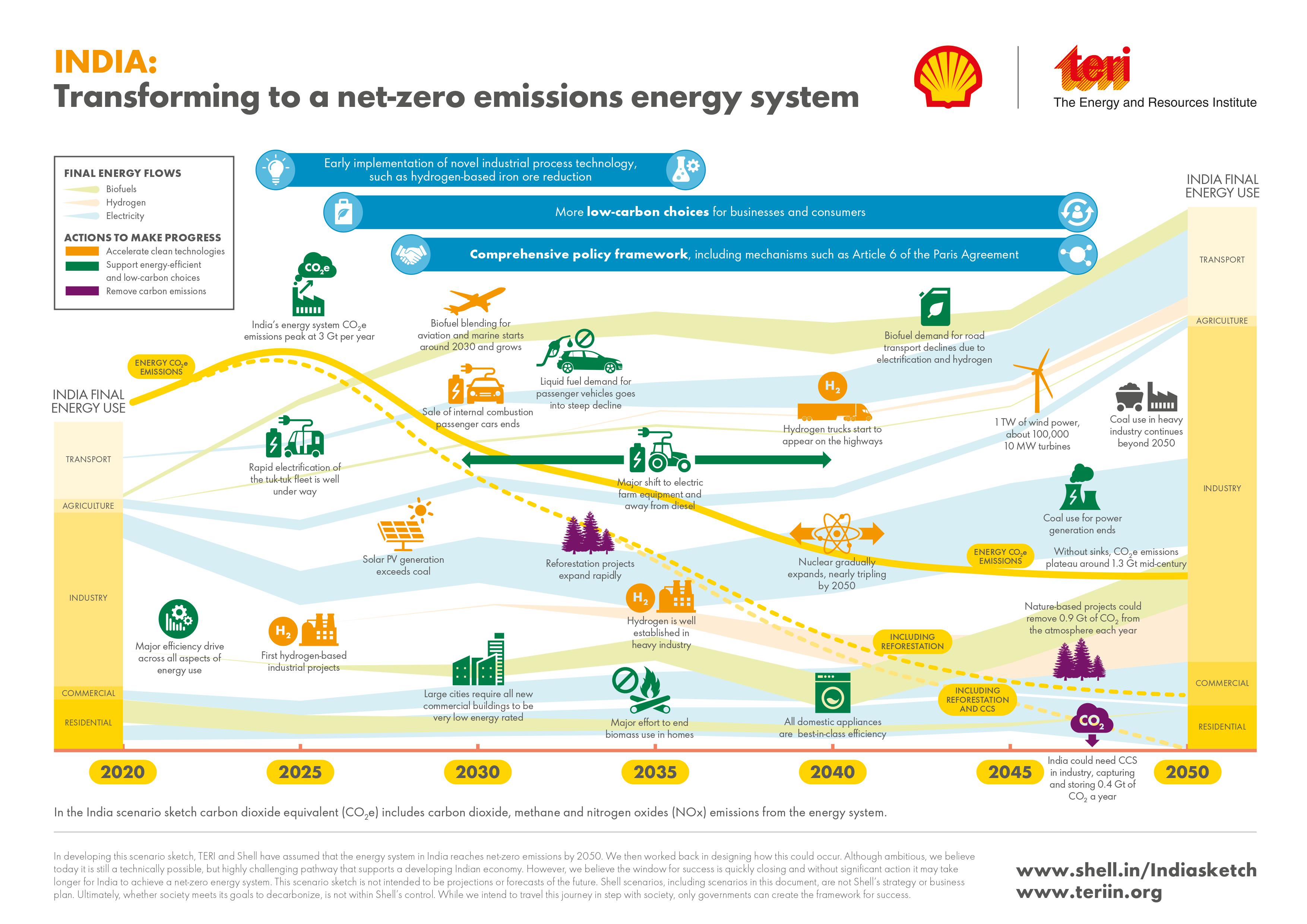

But what might such a development pathway look like? Over recent months the Shell scenario team and Shell India have worked with The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) of India to illustrate what the future could hold. In this collaboration the team developed a Net-Zero Emissions (NZE) scenario, the principle focus of the work, to examine whether adequate opportunities exist to fully decarbonise the energy sector; areas where India’s energy sector does not have enough choices for full decarbonisation by 2050 are also highlighted. From a second scenario, Towards Net-Zero (TNZ), barriers to change that might emerge are revealed. Energy efficiency, electrification and a switch towards decarbonised fuels are the three main pillars of India’s energy strategy, with the need for a transformative move towards renewable electricity, hydrogen and bioenergy as key fuels. This analysis indicates that the industrial and heavy transport sectors are likely to face limits in achieving full decarbonisation, primarily due to technological constraints which leave residual emissions in the system. This necessitates the need for carbon removal options to achieve net-zero emissions, including both technical and natural solutions.

An overview of the pathway reveals both radical and very rapid change. For example, in India today, there is a successful programme of solar PV installation under way, but by 2030 as solar starts to dominate the generation mix in the NZE scenario, it will need to be matched by large-scale energy storage to manage intermittency. More than 1,000 gigawatts of solar PV, 700 GW of which with matching storage, needs to be installed through the 2020s, far exceeding the amount of solar PV installed over the last decade. This level of deployment is challenging, even in global terms. In 2019 global solar module production was about 140 GW, but growing at some 20% per year. Even if growth continues at this rate through the 2020s, the demand in India for modules under NZE would still equate to 20% of global supply. Embodied within the pathway is a monumental challenge, but one that is worth aiming to achieve.

The scenario analysis was released last week and can be under article named: INDIA: TRANSFORMING TO A NET-ZERO EMISSIONS ENERGY SYSTEM; Energy and Innovation segment of www.shell.in.The analysis incorporates both the pathway forwards and the policy framework required to get there.

Note: Scenarios don’t describe what will happen, or what should happen, rather they explore what could happen. Scenarios are not predictions, strategies or business plans. Please read the full Disclaimer under article- INDIA: TRANSFORMING TO A NET-ZERO EMISSIONS ENERGY SYSTEM, Energy and Innovation segment of www.shell.in

David Hone

David Hone works for Shell International Ltd. and is the Chief Climate Change Adviser in the Shell Scenarios team. He joined Shell in 1980 after graduating as a Chemical Engineer from the University of Adelaide in South Australia. He initially worked for Shell as a refinery engineer in Australia and The Netherlands, before becoming the supply economist at the Shell refinery in Sydney. In 1989 David transferred to London to work as an oil trader in Shell Trading and held a number of senior positions in that organisation until 2001. In that year David took up the role of Group Climate Change Adviser.

David was Chairman of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) from 2011-2013, a global business organisation of some 140 companies and remains a Board member. The Association focuses on the development of carbon markets. He is also on the Board of the Washington based Centre for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) and the Board of the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute (GCCSI) in Melbourne, Australia.

David posts regular stories on his energy & climate change blog, which can be found at http://blogs.shell.com/. He is the author of a 2017 book on climate change, ‘Putting the Genie Back: Solving the Climate and Energy Dilemma’.

NEWSLETTER

TRENDING ON PRO MFG

MORE FROM THE SECTION